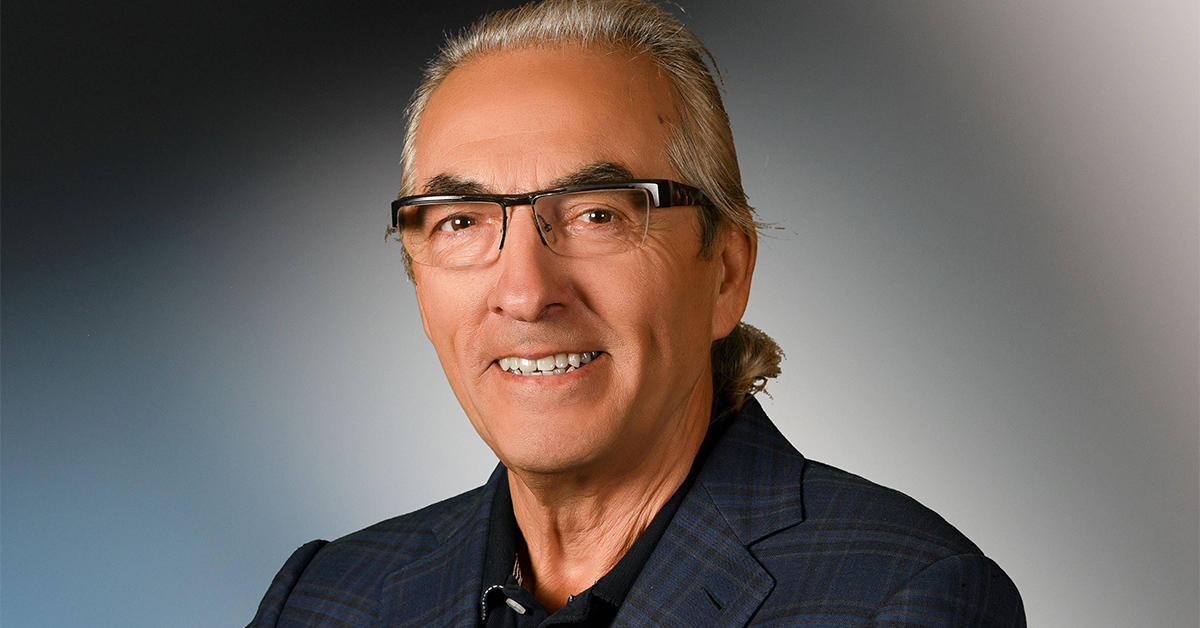

“Very seldom did we speak or hear people speak negatively of the school, the priests and the nuns. But there was a current that ran through our community. It was not healthy; it was troubling,” said Phil Fontaine, former National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), who spoke at an online uOttawa event on September 30 to mark the first annual National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.

Born in 1944, Fontaine is Anishinabe from Sagkeeng First Nation in Manitoba. He attended residential schools in Winnipeg and in his home community. Although his siblings, parents and paternal grandmother were all residential school survivors, he says that the abuse they experienced was not openly discussed.

“When it finally started seeping out, the shame and the sense of embarrassment prohibited people from talking openly.”

Confronting the shame

Fontaine was elected Manitoba regional chief for the Assembly of First Nations in the 1980s and elected grand chief of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs in 1991. In 1990, he first spoke publicly about the physical and sexual abuse he had experienced at the Fort Alexander Indian Residential School.

“We always talked about the future and what the First Nations community would become,” he recalled. “We wanted this good, beautiful, thriving community to emerge. And I said to myself, ‘We’re not going to make that come about if we allow this dark cloud to overshadow everything that we’re doing.’”

At the AFN annual meeting in Whitehorse in 1990, where Fontaine shared his story, he made the point that “we had to confront this issue — as shameful, painful and embarrassing as it was going to be. It was our responsibility to do so.”

Becoming whole

The courage of survivors to speak about their experiences led to Canada’s national apology in 2008 and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, active from 2009 to 2015.

As Fontaine had said on CBC’s The Journal October 30, 1990, “We’re hoping that the step that I've taken will make it easier for others to talk about their experiences.”Addressing the abuse and documenting this collective experience was important, he said, “so that we never forget about it… But, as well, to undertake a healing process to make our people whole.”

As national chief of the AFN from 1997 to 2000 and from 2003 to 2009, Fontaine played a key role in negotiating the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, which came into effect in 2007. It was the largest class action settlement in Canadian history, involving 20 cases and more than 15,000 individual claims of sexual and physical abuse.

In 2008, during Fontaine’s third term as national chief, he and other Indigenous leaders and survivors heard then-prime minister Stephen Harper offer a formal apology for the residential schools in the House of Commons.

The power of education

Darren Sutherland, uOttawa’s Indigenous community engagement officer, asked Fontaine to discuss how education in Canada has changed in response to the national conversation on residential schools.

The resilience of survivors and their descendants in the face of cultural destruction through residential schools has been expressed in Indigenous peoples’ view of schooling and education as a path forward.

For Fontaine, education provides a person with the tools they need to live a full life. He is encouraged to see that school curriculums across the country are now teaching Indigenous histories and ways of being.

“Who’s running most of our communities? Educated people who are in no way interested in dismissing or discarding cultural interests, practices, our languages,” Fontaine says.

The Indian Act was only changed in 1961 so that First Nations people could graduate from university without losing their Indian status. Today, universities across Canada have strategies to welcome Indigenous peoples and bolster their cultures. In Ontario, there are now over 20,000 Indigenous postsecondary students. This includes 500 at uOttawa, which has an Indigenous Action Plan.

“We absolutely know that the best way we’re going to continue to achieve great success is collaboration,” said Fontaine. “It’s our responsibility to teach Canadians about ourselves, about what is important to Canada’s future. Clearly, a central piece in this is Indigenous peoples. Our cultural integrity, our traditional practices. Gosh, we have so much to offer.”

This event was presented by the Indigenous Affairs Office, Mashkawazìwogamig Indigenous Resource Centre, Institute of Indigenous Research and Studies, Indigenous Students Association and Indigenous Law Students Governance.