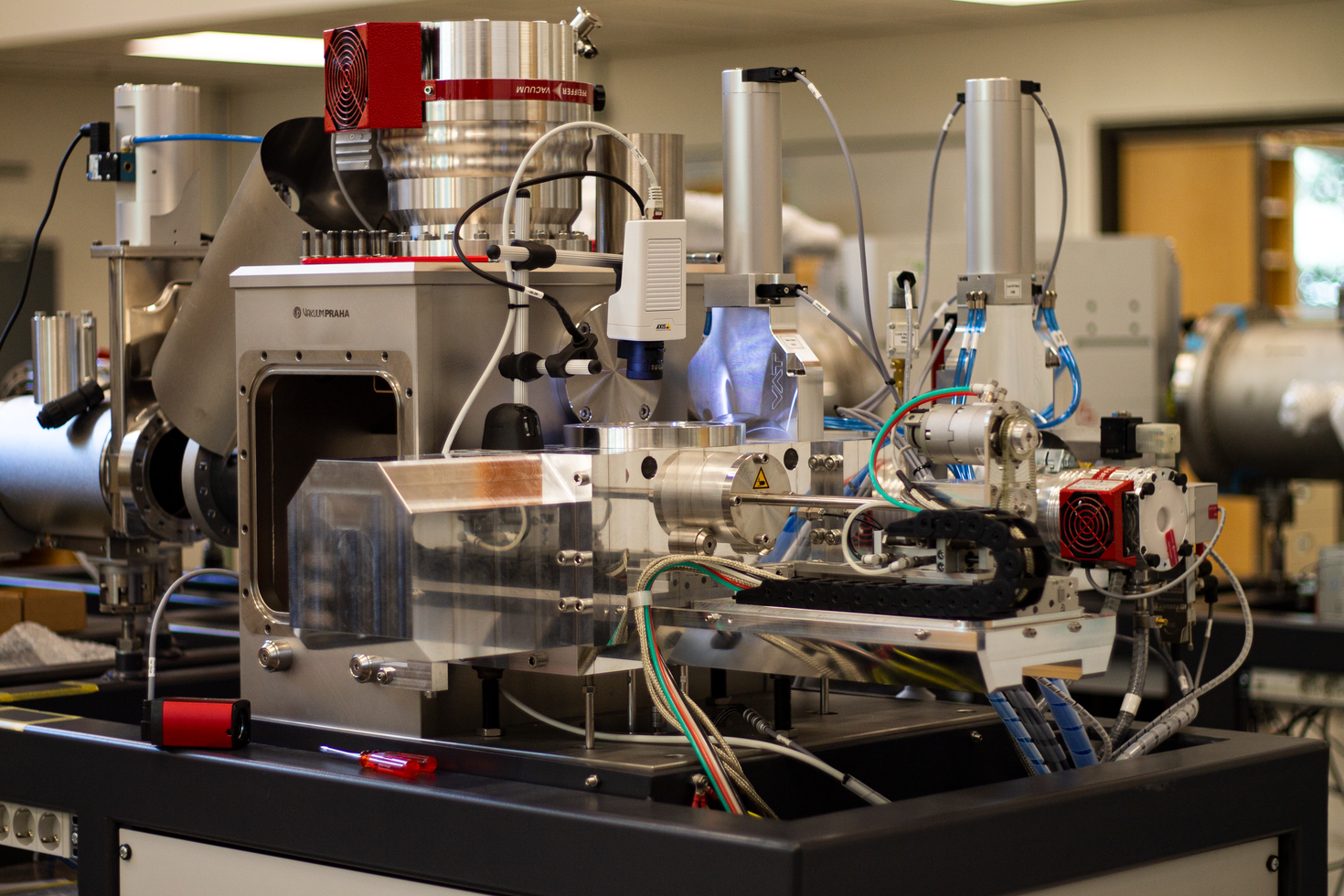

In a recently published paper, Dr. Gary Salazar and Dr. Len Wassenaar examined 2.5 years of data from samples processed on the Mini Carbon Dating System (MICADAS) machine at the André E. Lalonde National Facility for Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS). After analyzing almost 8000 data points, they notice something “fishy”.

When counting radiocarbon on an AMS, it was assumed that the results should follow a Poisson distribution. Simply put, a Poisson distribution is one way to model how likely we are to measure a certain number of radioactive isotopes over a fixed amount of time.

The results, published in the journal Radiocarbon, show 63% of the time radiocarbon counts followed a Poisson distribution as expected, but 37% of the results did not. Luckily, about 34.2% of the 7985 samples were only slightly off a Poisson distribution, but 2.8% missed the mark completely.

When reporting radiocarbon dates scientists must always include error ranges. What Salazar and Wassenaar discovered, is that assuming a Poisson distribution to calculate errors might not be the best idea. Their research found a quasi-Poisson model did a slightly better job of accounting for all the error in the data than a regular Poisson model would. Using a quasi-Poisson model to calculate errors does produce a slightly larger date range of uncertainty for radiocarbon dates, but the authors argued that is more reflective of the true error of the data.

Salazar and Wassenaar cautioned that their findings are specific to their MICADAS machine, but they challenge other AMS laboratories to replicate their work to see if their data also has the same unexpected “less-than Poisson” results.