It has been an exciting year for Thomas Burelli, Professor of Environmental Law in the Civil Law Section, and it is capped off as he receives a PhD in Law at uOttawa’s 2020 Spring Convocation.

His research was aimed at studying collaborative relationships between scientific researchers and Aboriginal communities, with the goal of establishing equitable and respectful relationships between them. He sought to contribute to the evolution of these relations by drawing on the best practices developed in Canada.

«In the past, I had observed the attitudes of researchers towards Aboriginal communities and their knowledge - an arrogant and contemptuous attitude. That's what made me want to dig deeper into these relationships. »

His work, carried out under the supervision of law professors Sophie Thériault and François Féral, contributes to the fight against biopiracy. This is what happened recently in New Caledonia, where he took part in the resolution of a conflict between the Parfums Christian Dior company and an indigenous people of this Oceania archipelago.

Par Johanne Adam

During the 1990s, Parfums Christian Dior patented six plants native to New Caledonia with the goal of integrating them into their high-end cosmetic products. However, the luxury brand had learned of the medicinal properties of these plants from the Kanak, the people indigenous to this Pacific archipelago.

The circumstances surrounding Dior’s appropriation of these plants eventually resulted in a conflict between the multinational company and the local population.

Some two decades later, on November 30, 2019, Dior and the Customary Senate of New Caledonia issued a joint statement in which they indicated that they had found common ground. Thomas Burelli, who teaches environmental law at the Civil Law Section of the Faculty of Law, University of Ottawa, played a major role in resolving this conflict.

For the time being, the details of these discussions and their consequences remain confidential.

A lengthy endeavour

The joint statement is the result of painstaking efforts by Thomas Burelli.

It all started in the early 2010s, when Burelli was conducting research on biopiracy, which is the non-consensual use of traditional indigenous knowledge, particularly knowledge used in traditional medicine.

“I was conducting a literature review of research projects dealing with traditional knowledge when I came across some very problematic cases of Kanak knowledge being used to identify and benefit from these plants.”

During the 1990s, France’s Institut de recherche pour le développement (IRD), a public research agency, conducted studies on these plants. The results of these studies, made possible thanks to local indigenous knowledge, were later ceded to Dior.

“At the time, this practice was very widespread: there are many such cases documented in the academic literature,” said Thomas Burelli.

Burelli’s first reaction was to ask Kanak authorities if they were aware of the situation.

Discussions to find a solution

“During a field study in 2015, I met with the Customary Senate of New Caledonia, an assembly of representatives from the various traditional councils of the Kanak people. They were very familiar with these plants due to their medicinal properties. Some representatives remembered the research that had been conducted on their territory, but they were completely unaware that the knowledge they had provided to French researchers had being exploited in this manner.”

At that point, Thomas Burelli began working to rectify the situation: he first sought the approval of the Customary Senate. “This took a long time. I was alone and had trouble moving the case along.”

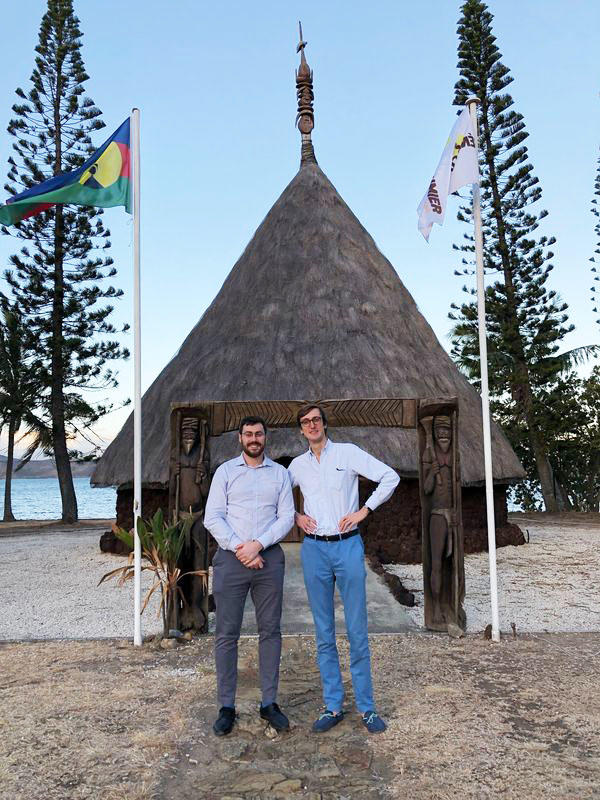

He then solicited help from Louis-Romain Riché, a member of the Paris Bar Association. Together, they met with representatives from Dior and initiated the discussions that would result in the joint statement.

“The company’s approach was very respectful and constructive during our discussions. I was very impressed by Dior’s openness and growing awareness of the issues,” said Burelli.

Acknowledgement of traditional expertise

In the joint public statement issued by the Customary Senate and Parfums Christian Dior, the company restates that it supports the Kanak people’s right to protect their traditional knowledge.

“Parfums Christian Dior wishes to hereby reaffirm its respect for the rights of the Kanak people over the biodiversity of their territory from the dual standpoint of acknowledging their traditional know-how and protecting the environment.”— Parfums Christian Dior.

For their part, Kanak representatives said they felt honoured by the statement. However, they maintain that this kind of situation must never reoccur on Kanak territory.

“This situation highlights the long-term impact of colonization on indigenous peoples. Moreover, the restitution underscores the value that indigenous cultures can bring to international research,” said Cyprien Kawa, tribal chief and member of the Customary Senate of New Caledonia.

For Thomas Burelli, the process has made history in France’s overseas territories. “The resolution of this issue is a first in France and I am very pleased with the outcome after four years of discussions.”

A code of ethics

However, Burelli’s efforts are not over; he continues to work to foster more equitable relations between indigenous communities and the researchers seeking their traditional knowledge. In fact, the doctoral research he completed in September 2019 focussed on this topic.

“I noticed that in France, there are practically no guidelines to structure research that involves indigenous peoples, while in Canada, there are many such instruments.”

During his stay in New Caledonia, Thomas Burelli shared the results of his research, including a project to develop a code of ethics for studies involving indigenous communities. He submitted this code to both the Conseil National du Peuple Autochtone de Kanaky-Nouvelle-Calédonie (the national council for the indigenous people of Kanaky–New Caledonia) and the Agence de développement de la culture kanake (a Kanak cultural development agency).

“Many things have evolved since I started my research in this field in the early 2010s. Several misuses [of traditional knowledge] have been successfully exposed and innovative tools are beginning to emerge. Local actors have become aware of their agency, including their right to refuse research projects and to impose conditions on researchers. I am very hopeful that relations between researchers and indigenous peoples in France’s overseas territories will undergo a positive transformation.”