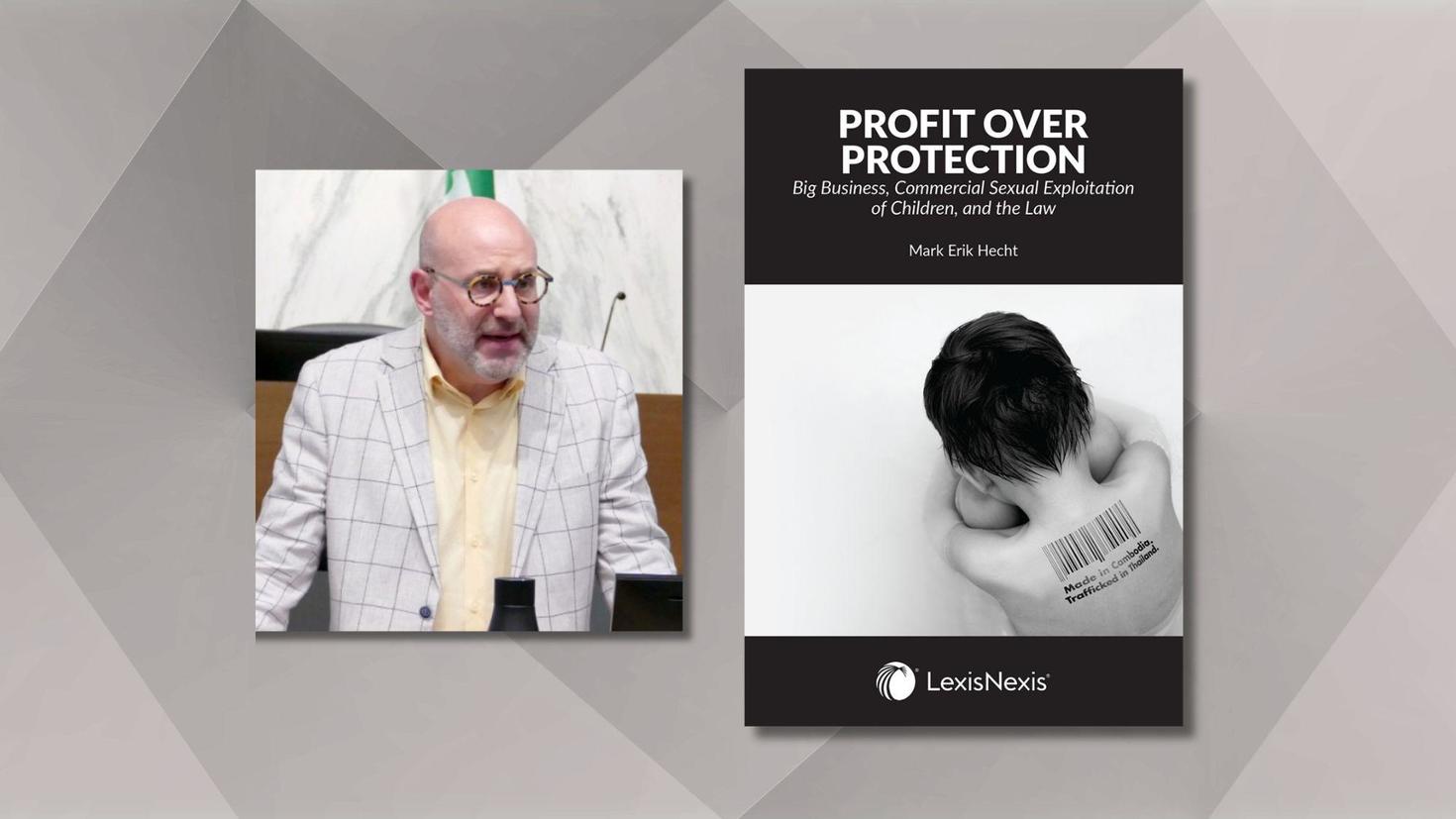

For University of Ottawa law professor Mark Hecht, this paradox has driven 20 years of research and advocacy. He has seen how the commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) can leave survivors with physical injuries and emotional trauma while offenders take advantage of loopholes that make prosecution a game of jurisdictional “whack-a-mole.”

“We’ve focused so much of our energy on holding governments accountable that we missed the ball,” he says. “We haven't held the private sector accountable.”

He proposes a new international framework to enforce corporate accountability.

Why existing laws fall short in protecting children

Human rights legislation may look robust but is equally challenging: it generally applies only to state actors, not to corporations. This oversight creates an opportunity for private sector entities to engage in or facilitate CSEC almost with impunity.

No sooner does a government investigate and shut down a business in its own jurisdiction than another takes its place somewhere else. The cycle repeats, with industry players often insulated by the lack of international enforcement.

Silence and the industries that enable abuse

Hecht says offenders operate in industries where children are most likely to be isolated, such as travel and tourism, entertainment and online gaming. Underlying the abuse itself are credit card companies and online payment platforms that process financial transactions with few, if any, questions asked.

Silence is another obstacle. Global hotel chains have historically been reluctant to confront trafficking or sex tourism publicly, even if they’ve never been implicated, out of concern for damage to their brand and share price. Taxi drivers, bar owners and guides who depend on local visitors stay quiet to protect their livelihoods, and in some cases their personal safety.

Generative AI brings new risks

The newest threat comes from generative AI. Tools for nudifying, voice cloning and de-aging can create explicit images of children, even if no actual child was involved.

These new tools raise new questions about harm, liability and the need to create legal definitions for AI that didn’t even exist a few years ago.

“Right now, it’s a free-for-all,” says Hecht. “There are no laws or regulatory guardrails around any of this. The companies creating AI today are operating at light speed; questions about child safety aren’t even being asked.” In response, his team has begun work on a new legal vocabulary for CSEC in the age of AI.

Signs of progress, but too fragmented

Despite challenges, some industries have taken steps forward. Many hotel chains train their staff to recognize signs of potentially abusive situations and take discreet action to intervene. Local managers implement zero-tolerance policies toward taxi companies to discourage facilitating sexual encounters with children.

More broadly, French hotel chain Accor has made its WATCH Program (We Act Together for CHildren) a core element of its corporate social responsibility program. In 2022, VISA cut ties with MindGeek (now known as Aylo Holdings and owner of the adult website PornHub) over allegations that the site hosted sexually explicit videos of minors. And in June 2025, the European Parliament voted to abolish time limits on the prosecution of child abusers – a significant step forward for survivors.

But Hecht cautions that these initiatives remain fragmented and that their impact will be minimal and short-lived unless they’re backed by international law. “We know the problem is international. We need an international solution to hold the private sector accountable,” he says.

“We know the problem is international. We need an international solution to hold the private sector accountable.”

Mark Hecht

— University of Ottawa Law Professor and author

A bold call for collective action

Hecht is now pushing for a new protocol under the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child that would oblige multinationals to abide by the same laws that countries do.

Such a change would give national governments the legal authority to target offenders and provide a framework for coalitions to engage in collective action.

Hecht knows there’s no quick fix to eradicate CSEC. But he also knows what’s needed to make meaningful and lasting progress.

He also stresses responsibility also falls closer to home: parents, relatives and teachers have a responsibility to protect children in their care, and to listen to them if they seem troubled. Citizens, too, can support companies like Accor that have been open and transparent in their efforts to combat CSEC.

“Everybody has a role to play,” Hecht highlights.

Profit Over Protection: Big Business, Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children, and the Law (LexisNexis Canada 2025) is available now.