In English Canada, the idea might sound strange. But for Ontario’s French-speaking minority, sports have long been a bridge between language and identity.

In this episode of Parlez-moi de l’Ontario français, Professor Christine Dallaire, a researcher at uOttawa’s School of Human Kinetics, and Félix Saint-Denis, a cultural activity organizer and proud advocate for Franco-Ontarian identity, explore how the Jeux franco-ontariens — or the Franco-Ontarian Games — became one of the most powerful tools to strengthen community pride among Francophone youth.

Speaking French on the field

In the early 1990s, sports were everywhere. Hockey, volleyball, basketball — they were all popular spaces for teenagers to bond. But for French-speaking teens in Ontario, those worlds existed almost exclusively in English.

So, when FESFO (the Fédération de la jeunesse franco-ontarienne, an organization representing Francophone youth) created the games, it did something revolutionary: it brought French onto the field.

“Sports had nothing to do with language,” explains Dallaire. “So, to play in French — to hear your coach and your teammates speak French — it gave the language a new life.”

Reinventing the model

Unlike other Francophone events in Canada, FESFO’s Franco-Ontarian Games were never just about competition.

Instead of schools sending full teams, each school would send just two students: one boy and one girl. They would then be mixed into new teams on site, joining peers from across the province.

“You’d have someone from Hearst playing with someone from Toronto, Windsor or Rockland,” says Dallaire. “The goal was to create friendships, not rivalries.”

And the games weren’t just for sports. They were multidisciplinary, combining athletics, improvisational theatre and visual arts. This blend celebrated every kind of talent.

“More than a competition — a movement”

For Félix Saint-Denis, then a youth leader at FESFO, the games were about leadership and identity, not medals.

“The games were first and foremost an exercise in leadership and pride,” he says. “Sports were just one part of it.”

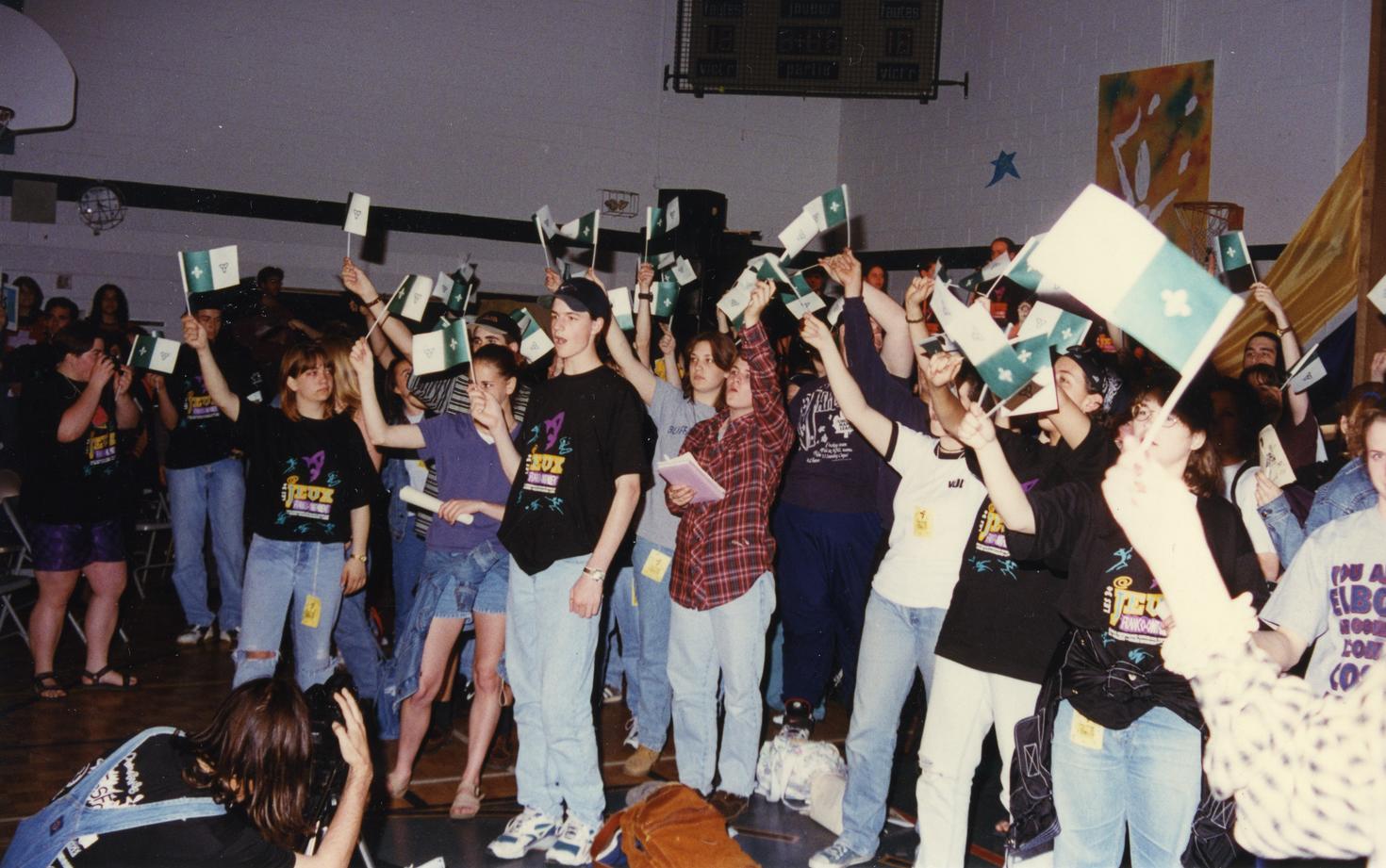

He recalls the first edition in 1994, when Franco-Ontarian singer Paul Demers performed “Notre place” and the green-and-white Franco-Ontarian flag was raised for the first time.

“It gave people chills. You could feel that something was changing. You could be Lebanese and Franco-Ontarian, Anglophone and Franco-Ontarian — and proud of both,” he explains.

Co-operation, performance and pride

Three words guided the spirit of the Games: co-operation, performance and pride.

Teams overcame the divides of school or region, united by a shared language. And for many participants, it was the first time they’d experienced fun in French.

“It wasn’t about making French feel mandatory,” says Saint-Denis. “It was about making it joyful — something you wanted to live, not something imposed on you.”

Defining moments

One of Dallaire’s favourite memories is from the 2001 games in Windsor. During the opening ceremony, students re-enacted the history of Francophone Ontario. The first character: Mathieu da Costa, an African interpreter for French explorers in the 1600s.

“It was a bold statement,” she recalls. “It showed that Francophone identity isn’t about skin colour or origin — it’s about the desire to live in French.”

Saint-Denis remembers a different scene: a high-jump final where the crowd cheered just as loudly for both competitors.

“Even the coaches said, ‘We’ve never seen that kind of sportsmanship.’ That’s what the Games were about — shared pride, not rivalry,” he says.

After the pause

The Franco-Ontarian Games stopped after 2019 due to the pandemic. But both guests believe their spirit remains vital.

“Young people need to gather in person again,” says Dallaire, “to feel connected and experience strong emotions.”

“My wish,” adds Saint-Denis, “is that we celebrate the Franco-force of our diversity so fully that we never have to use the word ‘diversity’ again.”

Passing the torch

Today, it’s up to a new generation to reinvent what these gatherings look like. The message from their predecessors is clear:

Sports can build community.

Culture can build pride.

And together, they can shape a language that lives, breathes and belongs — on every field, on every stage and with every voice that dares to speak it.