“Music has a remarkable way of bringing people together,” she says. “Timothy’s artistry is extraordinary, and his work to democratize classical music and open it up to more people resonated with me. I wanted the installation to carry that same spirit — excellence paired with inclusion, creativity shared openly.”

Chooi was struck by her optimism and her genuine support for the arts in general and for the creative work and research happening at the School of Music.

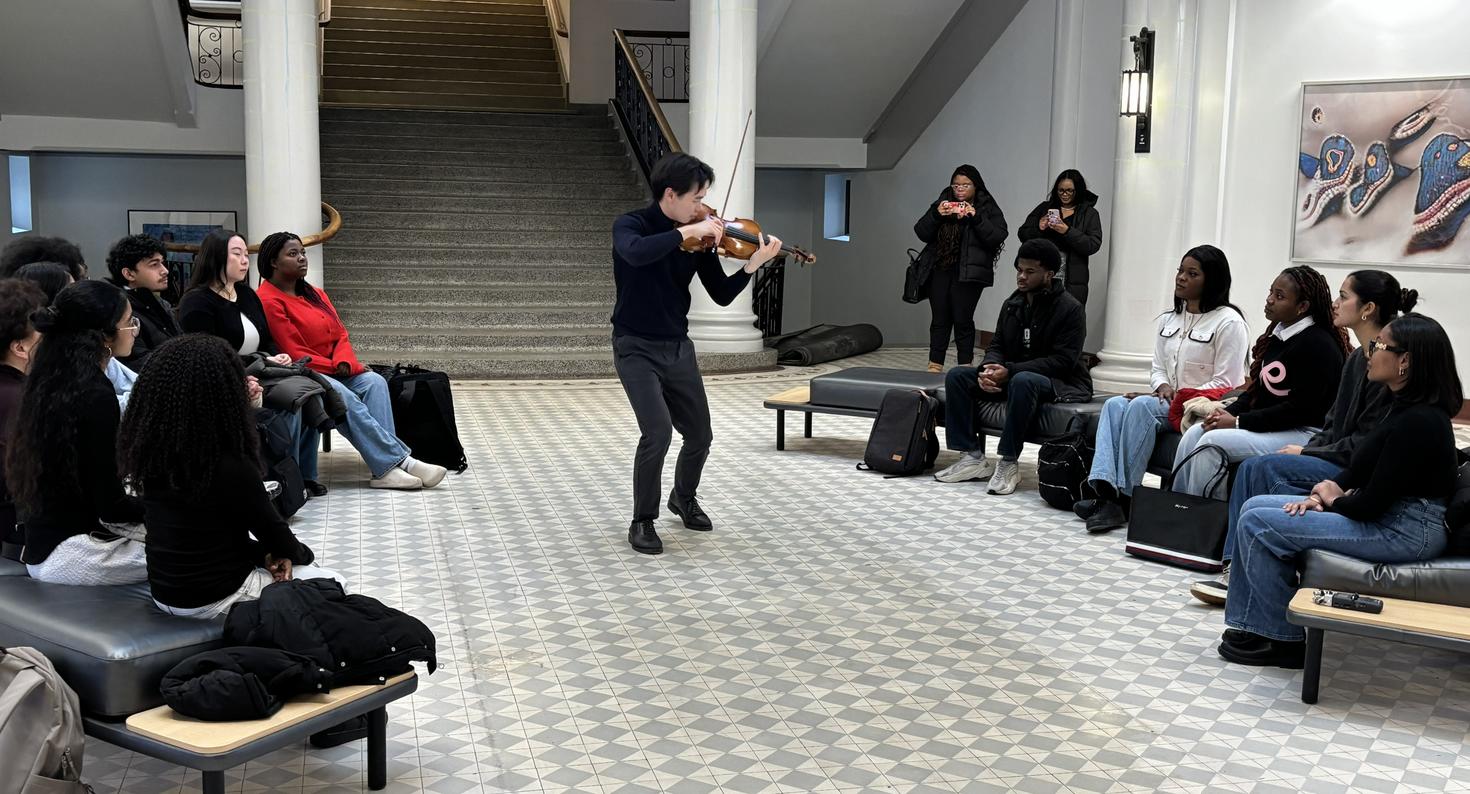

A conversation like this naturally frames how you listen to the music that played during the installation. The combination of the piece selected and the instrument used to play it embodied the president’s vision and illustrated the issues at the heart of Chooi’s social, musical and inclusive research. The installation featured a rare privilege—the opportunity to hear the 1714 “Dolphin” Stradivarius, one of only three in the world and the only one still being played, on loan from the Nippon Music Foundation and entrusted to one of our own professors.

Classical music growing into a more inclusive and connected future

Classical music is growing more inclusive and forward looking, qualities that are deeply rooted in Chooi’s artistic and scholarly work. His research examines how classical music can strengthen social connection, spark conversations between different traditions, and create space for voices that have often been absent from the field. His research efforts, which blend community engagement, cultural listening and performance-led inquiry, were recently recognized with the University’s Equity, Diversity and Inclusion in Research Award.

For Chooi, musical performance is inseparable from that research. Whether he is designing a program for major concert halls such as Carnegie Hall or the Concertgebouw Amsterdam, or working with communities in remote regions across Canada and around the world (most recently in Mexico and Japan), his artistic choices are continually informed by encounters that remind him that classical music is most meaningful when it creates a space for people to see themselves in it.

“Those experiences guide how I approach repertoire, how I think about interpretation, and how I imagine classical music growing into a more connected and inclusive future.”

This lens also shaped the way Chooi approached the repertoire for the installation: he wanted a piece that welcomed listeners into the moment, carried cultural layers and reflected his belief in music as a shared space of connection.

“Those experiences guide how I approach repertoire, how I think about interpretation, and how I imagine classical music growing into a more connected and inclusive future.”

Timothy Chooi

— Violinist and professor, Faculty of Arts

A piece rooted in community: Bartók’s Romanian Folk Dances

For the installation ceremony, Chooi selected Romanian Folk Dances by Béla Bartók, a work that emerged during a turning point in the composer’s life. As Bartók stepped outside the concert hall and into rural communities, he encountered music that was lived rather than performed. These were melodies shared in homes, fields and village gatherings. The experience reshaped his musical language and reminded him that classical music becomes more alive, more honest, when it listens to the cultures and communities surrounding it.

Chooi sees that history reflected in the piece itself: its rustic rhythms, modal colours and expressive clarity bridge the gap between folk energy and classical craft in a way that feels both grounded and expansive.

“There’s something immediate and human about these dances,” he explains. “Their rustic rhythms, their intimacy, and the clarity of Bartók’s writing all remind me that even the highest forms of classical music are, at their core, rooted in community.”

For Chooi, Bartók’s blend of folk vitality and classical craft is the perfect musical metaphor for the installation — a reminder that shared beginnings are shaped by many voices coming together.

A legacy in motion: the 1714 “Dolphin” Stradivarius

Chooi performed the Bartók work on the 1714 “Dolphin” Stradivarius, widely recognized as one of the most remarkable instruments from Antonio Stradivari’s Golden Period. For Chooi, playing the Dolphin is both humbling and energizing. The violin has been held by pioneers such as Jascha Heifetz, whose early recordings defined the sound world of the 20th century and carried classical music into living rooms and concert halls around the globe. Each musician who played it afterwards — from Akiko Suwanai to Ray Chen — added colour to the instrument’s voice.

“To now play this 311-year-old instrument, thanks to the generosity of the Nippon Music Foundation, feels like stepping into a living, breathing lineage,” Chooi says. “Its past is extraordinary, but what moves me most is knowing that its story is still unfolding here, in Canada.”

For Chooi, the Dolphin’s arrival at the University of Ottawa carries its own significance. He feels a responsibility to honour the instrument’s long tradition with integrity and curiosity, while contributing something meaningful for whoever holds it next when it moves on to new hands, new countries and new generations of listeners.

In this collective moment, the instrument became part of the story the ceremony marked: a story about continuity, reinvention and possibility, carried across generations and cultures. “I hope the performance helped people feel connected — to the moment, to each other, and to the possibilities ahead,” says Chooi.